Ireland has just issued a postage stamp commemorating Che Guevara. Featuring the ubiquitous two-tone portrait created by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, the stamp marks the 50th anniversary of Guevara’s death on October 9, 1967. The postal service’s rationale is that Guevara had Irish ancestry and that Fitzpatrick’s artwork “appears on t-shirts, posters, badges and clothing worldwide and is now rated among the world’s top 10 most iconic images.”

Ireland has just issued a postage stamp commemorating Che Guevara. Featuring the ubiquitous two-tone portrait created by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, the stamp marks the 50th anniversary of Guevara’s death on October 9, 1967. The postal service’s rationale is that Guevara had Irish ancestry and that Fitzpatrick’s artwork “appears on t-shirts, posters, badges and clothing worldwide and is now rated among the world’s top 10 most iconic images.”

And they’re certainly right about that last bit. Guevara, the erstwhile Marxist revolutionary, has acquired cult-like status. Even more, he’s become a fashion accessory.

There is, however, a mindless quality to this.

Reflect on the question of who Guevara actually was and you’ll be struck by the extreme dissonance between the real man and the values that modern progressive opinion claims to hold dear. If you value freedom, democracy, tolerance, dialogue, inclusiveness, peace and love, then know this: Che Guevara would have despised you.

Born in Argentina in 1928, Guevara came to fame as one of Fidel Castro’s key confederates during the late 1950s Cuban revolution. He was killed by the Bolivian army in 1967.

And what was Guevara doing in Bolivia? He was trying to start a civil war.

Describing Guevara as a “Marxist revolutionary” is an exercise in euphemism. Or to put it more bluntly, it’s a cop-out that conceals more than it reveals.

Guevara’s primary political instinct was totalitarian. He had a view of what society should be and wasn’t interested in other perspectives. Citing a famous 1965 Guevara essay, the historian Hugh Thomas characterised his contempt for “bourgeois democracy” as “obsessive.”

Guevara also had a propensity for violence. You might even say that he was infatuated with it.

Whether it was presiding over the firing squads at La Cabana prison in 1959 or his 1967 fantasising about “two, three or many Vietnams,” Guevara was most comfortable with, in his own words, “the staccato singing of the machine guns and new battle cries of war and victory.” Thomas put it this way: “At the end of his life, he seems to have become convinced of the virtues of violence almost for its own sake.”

Interestingly, though, there wasn’t much in the way of “victory” in Guevara’s final years. His 1965 intervention in the Congo ended ignominiously and the peasants he ostensibly went to liberate in Bolivia wanted nothing to do with him. By the time he was captured, he and the remnants of his ragtag guerrilla band were sick, isolated and abandoned.

What is it about Guevara that attracts people?

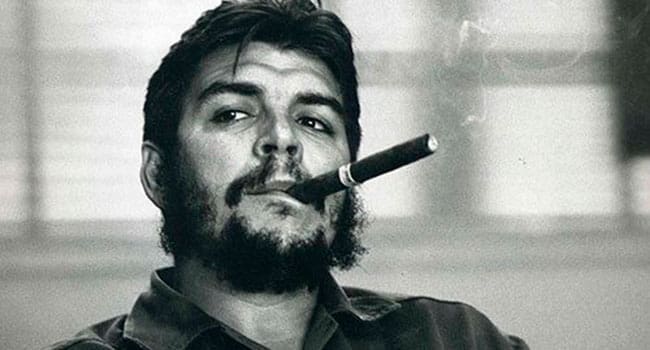

In the most obvious sense, it’s a matter of image. There’s no doubting that Guevara was a handsome man and the iconic portrait radiates a romantic charisma. Like all memorable pin-ups, it’s a canvas for projecting fantasy and proclaiming self-identity. You, too, can be a sexy rebel if you wear this t-shirt!

On a more serious level, some will argue that Guevara was the supreme freedom fighter. If you like, a liberator par excellence.

That, however, is pure nonsense.

If it means anything, liberation is about freeing people to be what they want to be, to live their lives according to their own choosing. Guevara wanted absolutely nothing to do with that. His interest was in transformation, creating a “new man.”

And if you didn’t want to be so transformed, that was your tough luck. Like it or not, he was going to transform you.

Nor is there plausible refuge in the proposition that Guevara was an idealist, albeit perhaps a naïve one. As designations go, that’s more than a tad disingenuous.

It would be more accurate to characterize him as an ideologically-driven utopian, someone akin to Cambodia’s Pol Pot or China’s Mao Tse-tung. To them, other people weren’t individuals with preferences and aspirations of their own. Rather, they were merely building blocks in a grand scheme.

Still, Guevara was certainly a brave man, personally unafraid of death. Indeed, one might reasonably wonder if he became enamoured with the prospect of dying.

When he confided in Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser about his desire to find “a place to fight for the world revolution and to accept the challenge of death,” the sympathetic Nasser asked if he couldn’t “live for the revolution” instead.

This, then, is the real man behind the peculiar cult. Oh, dear!

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.