Last fall, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario demanded that Sir John A. Macdonald’s name be stricken from all public schools in the province. More recently, Halifax city council voted to remove the Edward Cornwallis statue that had stood downtown since 1931. Both decisions were vigorously debated and public opinion remains sharply divided.

Last fall, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario demanded that Sir John A. Macdonald’s name be stricken from all public schools in the province. More recently, Halifax city council voted to remove the Edward Cornwallis statue that had stood downtown since 1931. Both decisions were vigorously debated and public opinion remains sharply divided.

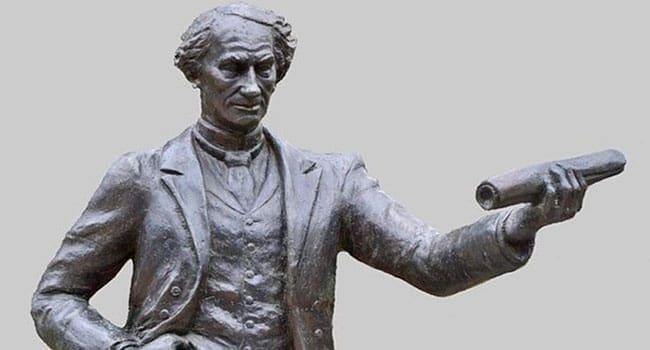

These are separate events about two different individuals. Nevertheless, the underlying theme is the same. Macdonald and Cornwallis stand accused of crimes against Indigenous people. Macdonald played a role in the establishment of residential schools while Cornwallis offered a bounty to anyone who captured or killed a Mi’kmaq person.

However, Macdonald and Cornwallis also have many defenders since both made significant contributions to their communities.

In order to think critically about Macdonald and Cornwallis, we need to know a lot of facts.

In Macdonald’s case, we need to know about the time in which he lived, his role as prime minister and the impact of residential schools on Indigenous people. People who know nothing about Confederation, Macdonald or residential schools are unlikely to have anything useful to contribute to this discussion.

Cornwallis was the military officer who founded Halifax in 1749. Like many other British officers of his time, Cornwallis saw nothing wrong with killing Indigenous warriors if they supported the French and appeared to be a threat to British colonists. Again, it’s necessary to know a lot about Cornwallis and the circumstances in which he lived in order to offer an informed opinion about his legacy.

There’s only one place where all Canadians, regardless of where they live, have a real opportunity to acquire the historical knowledge they need to think critically about these and other issues. The vast majority of students attend school and this is where Canadian history must be taught and learned.

Unfortunately, things aren’t that simple. Many educators downplay the need for students to memorize specific facts, particularly since information is widely available on the Internet. Instead, they want students to focus on so-called historical thinking skills through thematic study. This is largely the approach of Dr. Peter Seixas’s Historical Thinking Project, which has significantly influenced kindergarten-to-Grade-12 Canadian history education.

However, while broad-based historical themes such as change, continuity, cause and consequence are important tools for analyzing controversial issues, they’re not sufficient. Themes and overarching frameworks are useless unless they’re situated within a rich knowledge base. Thus, there’s still a place for teacher-led instruction and textbooks that place events in proper chronological order.

Twenty years ago, in his book Who Killed Canadian History?, renowned Canadian historian Jack Granatstein sounded the alarm about the lack of proper history education in schools. Granatstein argued that students were being shortchanged by social studies courses that presented a fragmented version of Canadian history. He wanted a much stronger emphasis on content knowledge that included the memorization of specific dates.

“The teaching of this content must be based on chronology, the basic tool of history. … Too much teaching in schools today takes a module of history and puts it before students to be digested, without much awareness of how it fits within a larger context,” explained Granatstein.

Among the four western provinces, only Manitoba requires all high school students to take a Canadian history course that puts key events in a proper chronological framework. While Saskatchewan has a mandatory Canadian Studies course for Grade 12 students, it’s primarily thematic in nature.

Even worse, Alberta and British Columbia don’t mandate Canadian history at all. Instead, they offer social studies courses covering themes such as ideology, genocide, nationalism and globalization. While these courses might be very interesting, they’re no substitute for a rigorous and chronological Canadian history course.

The governments of Alberta and B.C. are rewriting their curriculum guides. Unfortunately, all indications are that content knowledge will receive even less emphasis in the future than it does now. As a result, students will likely continue to learn an inadequate amount of Canadian history.

If we want Canadians to think critically about people like Macdonald and Cornwallis, we need to ensure they know the history of their country. Critical thinking best takes place in the presence of content knowledge.

Michael Zwaagstra is a senior fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and a public high school teacher.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.