Three things happened at Dunkirk, France, between May 26 and June 4, 1940, during the early days of the Second World War.

Three things happened at Dunkirk, France, between May 26 and June 4, 1940, during the early days of the Second World War.

First, the evacuation of more than 300,000 British and Allied troops made it possible to believe that Germany might be denied ultimate triumph. And that was an unambiguously good thing.

Second, the British won a symbolic victory that allowed them to draw defiant comfort from a military disaster. Combined with the heroic civilian contribution to the rescue, this birthed the inspirational “all in it together” spirit of Dunkirk.

And third, the Belgians got a bad rap. That wasn’t fair.

Launched on May 10, 1940, the German blitzkrieg engendered surprise, bafflement and panic. The Germans were suddenly everywhere. The Netherlands and Belgium were under withering assault, the mighty French army was reeling and the British Expeditionary Force was retreating to the coast.

On the morning of May 15, just five days into his premiership, Winston Churchill was awakened by a phone call from French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud. Reynaud had a stark message: “We have been defeated!”

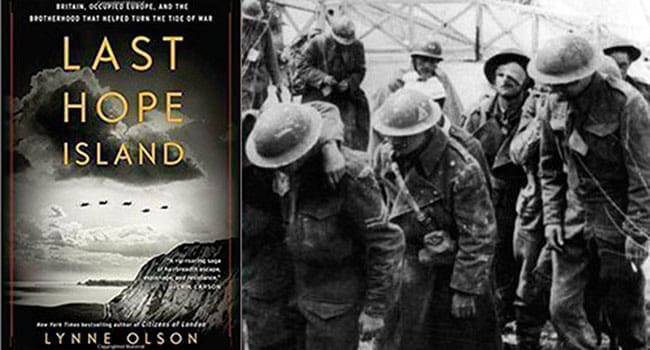

In her new book Last Hope Island, American journalist-historian Lynne Olson describes Churchill as “dumbfounded.” After all, the French army of two million men was supposedly the mightiest power on the European continent. Surely there must be a Plan B!

But there was no such plan.

On a flying visit to Paris the following afternoon, Churchill saw “utter dejection written on every face” at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In anticipation of impending disaster, officials were busy burning documents.

Olson describes the confusion: “Trained for static defensive warfare, the Allied military simply did not know how to react when the blitzkrieg … burst upon them. Co-ordination and communication between the French and British armies broke down almost immediately; within a few days, most phone and supply lines had been cut, and the Allied command system had virtually ceased to function.”

As things developed, the sense of looming defeat wasn’t confined to the French.

On May 26, a secret meeting of Britain’s inner war cabinet considered suing for peace. Two of the five members – former prime minister Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Edward Wood – were in favour. Churchill and the two Labour ministers – Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood – were opposed. To paraphrase the Duke of Wellington’s observation on the Battle of Waterloo, “it was a damn close-run thing.”

As for the maligning of the Belgians, it can be attributed to the need for a scapegoat. When disaster comes calling, shifting the blame is generally not too far behind.

True to its tradition, Belgium remained neutral until the German attack on May 10. Then it fought bravely but was no match for the opposition. So, on May 27, the Belgians gave the British and French a heads-up that surrender was imminent.

In the period between May 10 and the Belgian surrender, pleas to London for assistance were ignored. Churchill reported to the war cabinet, “the Belgian army might be lost altogether, but we should do them no service by sacrificing our own army.”

A similar approach was taken towards the French. Against the advice of the Royal Air Force, Churchill did accede to Reynaud’s request for 10 fighter squadrons to combat the Luftwaffe. But he drew the line there, turning down further pleas.

Instead, and keeping their allies in the dark, the British focus shifted towards retreat and evacuation. In effect, Churchill was counting on the Belgians and the French to hold off the Germans while the British escaped. Referring to the Belgians, he told a subordinate, “We are asking them to sacrifice themselves for us.”

Recounting this isn’t intended as a criticism. Churchill was being realistic.

If France and Belgium were going down, there was no point in Britain going with them. While it might have been a nobly romantic gesture, it would have delivered victory to Adolf Hitler.

However, that doesn’t mitigate the shoddiness of the subsequent rhetoric.

On May 28, Reynaud excoriated the Belgians and their king, Leopold III, for surrendering. Churchill followed suit on June 4. And in true Fleet Street fashion, London’s Evening Standard dubbed Leopold “King Quisling.”

But perhaps the cynicism gold medal goes to French Gen. Maxime Weygand. In Olson’s telling, Weygand believed the surrender had an upside as “we now shall be able to lay the blame for defeat on the Belgians.”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.