“I am only one, but I am still one,” Helen Keller said. “I cannot do everything, but I can still do something.”

“I am only one, but I am still one,” Helen Keller said. “I cannot do everything, but I can still do something.”

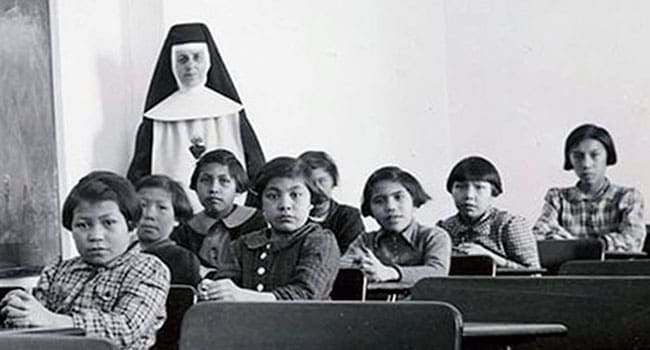

In 2008, the government of Canada created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate the residential school system in Canada and to give recommendations for moving forward as a nation. The commission’s findings, published in 2015, were groundbreaking. Ultimately, they referred to what happened in our country as “cultural genocide” and called for significant action to promote healing.

One key recommendation was in the area of education. Aboriginal learning thus holds a significant place in new curriculums across Canada. The challenge, however, is that few educators in Canada are Indigenous.

When we face challenges courageously, we always find solutions. I’ve experienced two very positive factors in promoting Indigenous education. First, the Indigenous educators I’ve worked with are exceptional. They ask if I would like to try different initiatives with my class, they answer my question, and they give me the supports I need. Second, I’m never made to feel like an outsider; I feel like an ally.

According to Indigenous writer and speaker Monique Gray Smith, “Being an ally means that you contribute to the healing, not to the hurting. Part of being an ally means that we listen deeply.”

Listening deeply is not easy, especially when the truth of what happened is so painful to hear. When we pass through that pain, however, we’re not only more empathetic to the suffering of others, we’re more determined to make a positive difference.

I’ve often heard about Indigenous children being taken from their villages by “Indian agents” accompanied by police officers. When I make an effort to truly listen to these stories, however, I’m changed.

As a parent, I’ve loved waking up and seeing my children smile. Sharing meals and laughter together are some of my happiest memories. It’s also meant everything to give them comfort when they were afraid and to help them to make sense of the world.

What if that were taken away from me? What if I couldn’t see them and spend time with them? What if they were taken to a place far away where they would cry themselves to sleep alone at night? What if I was aware that children died where they were going and I never knew if I would see my precious ones again?

These are painful thoughts, but fortunately for me, they’re only thoughts.

However, for many people in our country, those experiences – and even more horrific ones – were reality. For many, the scars of these events are still raw. Experience tells us that this type of wound can take generations to heal.

This type of listening expands me as a person. It inspires me to become an ally and to find new allies who will promote healing in our country.

As a teacher, truth is vital to everything I do. Truth enlightens all of us, regardless of our age or ethnicity. As we embrace truth, we embrace the first step toward reconciliation.

Embracing truth and reconciliation also helps me to realize that we’re all a part of something much larger. The mistreatment and abuse of children extends beyond residential schools, beyond the Indigenous community, beyond Canada and beyond history. As we embrace the story of one wounded person, we embrace an unfortunate universal reality.

We can’t eliminate all of this unnecessary suffering by ourselves but our role is still very significant. We can each do something and combined, that’s enough to heal the world.

Troy Media columnist Gerry Chidiac is an award-winning high school teacher specializing in languages, genocide studies and work with at-risk students.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.