Labour Day marks the unofficial end of summer. It’s back to routine and, once again, the workplace takes precedence. But what if there was no work?

Labour Day marks the unofficial end of summer. It’s back to routine and, once again, the workplace takes precedence. But what if there was no work?

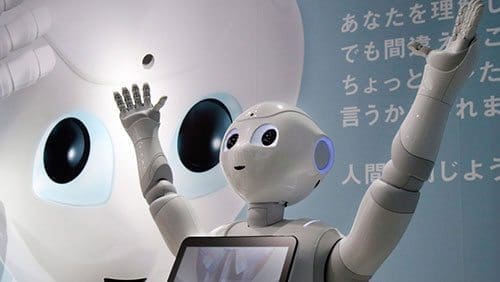

As automation and new technologies continue to reduce the labour force, economists and others are pondering this question.

Since 2000, the United States has lost five million manufacturing jobs and Canada has lost more than 500,000. According to a March 18 Canadian Press article, Canada will lose another 1.5 to 1.7 million jobs due to automation in the coming years.

Technology is also affecting jobs outside the manufacturing sector. Sophisticated software is reducing jobs in the financial and legal sectors. Routine banking no longer requires interaction with a live teller. Investing can be done online without the aid of a financial adviser. Equipped with the right software, computer-savvy young lawyers have less need of an assistant than their predecessors.

With the advent and rising popularity of the job-sharing or collaborative economy, other jobs are also in jeopardy. Airbnb has negative implications for employees in the hotel industry, as does Uber for taxi drivers. Jobs in the retail, and food and beverage sectors are also at risk – in the future, robots will ring up sales and bring drinks to the table.

While it may be politically expedient to blame globalization for the job losses, the real culprits are increased automation and investment in software. According to some predictions, half of all jobs in industrialized countries will vanish in the next 20 years due to automation, computerization, and advances in robotics and artificial intelligence. It will take time before new jobs replace those that are lost.

In the short term, the future may seem bleak as job trends point towards unemployment and underemployment. There will be some rocky times.

The ability to adapt, as individuals, communities and nations, will depend on a variety of factors. Education, job retraining and the development of public policy will be needed to address the tidal wave of change.

In this regard, some advocate that governments begin experimenting with ways to redistribute wealth, such as ensuring a universal basic income; supporting the growth of small business; investing in innovation; and creating and developing community-gathering places where people can connect with others to socialize, and to learn and pursue new skills.

It’s hard to imagine a world without work. From pre-biblical times, work has shaped society. Work has been such an integral part of the human experience that ancient Hebrew scholars sought to explain its existence in the Genesis myths of creation and the fall. Over time, the Judeo-Christian tradition developed a theology of work. Through work, humans become co-creators with God, shaping and transforming society and the environment. The theology recognizes a reciprocal relationship between the individual and work in which each impart dignity to the other. Work, it seems, is necessary for human thriving.

Psychology bears this out. Identity, meaning and purpose, as well as relationships, are closely linked to one’s work. Conversely, unemployment results in a loss of identity and purpose, depression, loneliness and isolation. In communities that experience widespread job loss, cultural breakdown and a loss of civic pride follow.

It may be time to rethink the understanding of work. What do we mean by work? And is paid work the only work that matters?

Society has come to associate work with a paycheque and income with status. Yet work doesn’t have to be limited to that which puts money in the pocket. Identity, purpose and meaning can be forged outside of the workplace. The workplace need not, nor should not, define one’s entire sense of self. Broadening the understanding of work to include activities beyond the workplace could have positive benefits for individuals and communities.

Work that’s a calling, volunteerism and caring for family members are activities that are either unpaid, poorly remunerated or generally undervalued in terms of their contribution to society. These activities, which are often labours of love, are deeply fulfilling. They reward one with a sense of purpose and accomplishment, shape the authentic self, promote relationships and enhance the development of society.

Redefining work is obviously not a panacea for widespread job loss. But a shift in thinking about the nature and role of work could help preserve the dignity of the jobless, while sparking creative solutions to problems in a rapidly changing world.

Louise McEwan has degrees in English and Theology. She has a background in education and faith formation.

Louise is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.