It’s hard for Canadian citizens to take the full measure of an American politician like John McCain, whose route to public service glory began in the combat of the Vietnam War. Our country doesn’t particularly valourize the military and those who serve, unless perhaps they do peacekeeping missions with the United Nations overseas.

It’s hard for Canadian citizens to take the full measure of an American politician like John McCain, whose route to public service glory began in the combat of the Vietnam War. Our country doesn’t particularly valourize the military and those who serve, unless perhaps they do peacekeeping missions with the United Nations overseas.

McCain’s career as a U.S. Navy pilot saw him shot down over Hanoi in 1967 as he flew his Skyhawk dive bomber on a mission that my youthful contemporaries at the University of British Columbia loudly mocked and opposed.

Young Canadians coming of age in the late 1960s were taught by national media and our university professors that the Vietnam War was an egregious extension of American capitalism and something to oppose at all costs. As a member of UBC student government in the early 1970s, I remember chartering buses to the American border at Blaine, Wash., so hundreds of students could gather and chant their shame at the U.S. citizens on the other side of the line.

Raised in a multi-generation American military family, with strong navy roots, McCain was the antithesis of my nascent Canadian hopes and wishes for the future.

Hustled off to the ‘Hanoi Hilton’ with two broken arms after his capture, McCain was lucky not to be summarily executed in the folds of his parachute when he was found by the Vietnamese Army regulars in the outskirts of Hanoi. Kept in a cell resembling a dog cage, McCain was regularly tortured and subsisted on a meagre rice diet. Offered early release because of his family connections (his father John S. McCain Sr. was a U.S. Navy four-star admiral), he declined.

Upon reflection nearly 50 years later, I should have internalized some youthful empathy for the young McCain and his military concept of national service. His country was at war. He signed up to serve. And when called, he did, with distinction. It was part of his family legacy: his father and grandfather were the first father-son pair to both achieve four-star admiral rank in the U.S. Navy.

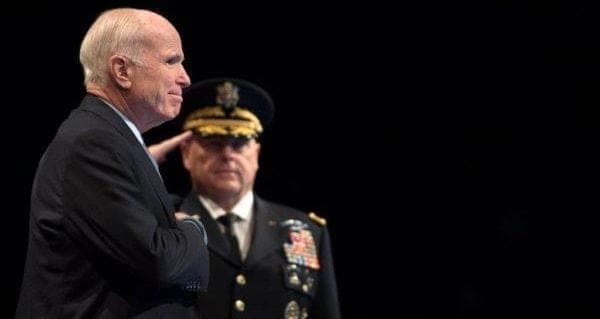

In his subsequent career as a six-term Republican U.S. senator from Arizona, McCain grew to become a liberal internationalist, strongly committed to the United Nations and the concept of global free trade. At the same time, he championed the old Republican virtues of value for money, economies of service, respect for opposing opinions, and a broad awareness of cultural differences and how they played out stateside and in the broader world.

One could say that he was culturally tolerant. Evidence of this was found again last week in the respectful commentary about him from the Vietnamese government,. Even his old Hanoi Hilton jailer remarked that he was a good man.

After the Vietnam War, he notably worked to expand U.S.-Vietnam trade and diplomacy.

Still politically active in his 70s and early 80s, McCain became the perfect foil for the legions of Americans and indeed global citizens who oppose the shameful pandering of Donald Trump to overt nationalism, trade isolationism, intolerance, despots and a common, vulgar style of communication.

While ostensibly both Republicans, McCain’s values of public service were first honed in his family, just as Trump’s were honed in his. So how can they both claim the same political party affiliation, and its once commonly-held values, as their base?

McCain’s roots are obviously in military service and Trump’s are in the New York version of property development. What values were inculcated in both little boys by their driven, hard-working, high-achieving fathers?

Presumably both were Republicans of the old school, the one that existed far before the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the European Union, the Tea Party revolt of the early 2000s, and the Great Recession of 2008. And far before the reform epoch of Barack Obama’s presidency, his financial aid to bankrupt homeowners and his government-sponsored universal health care.

I think the legacy Trump’s father gave his rich little boy is to mock government aid to those less fortunate, and to repudiate any championing of the role of government for human betterment, especially across borders.

McCain’s father’s legacy in his son was the value of military discipline and public service, especially across borders, in peacetime and in war.

Troy Media columnist Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.