On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union set the world agog with the launch of Sputnik, the first space satellite. And the pioneering achievement sent much of the United States into a panic.

On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union set the world agog with the launch of Sputnik, the first space satellite. And the pioneering achievement sent much of the United States into a panic.

Assumptions about American superiority in science and technology were suddenly called into question. The hostile Soviets were winning the space race and perhaps other races as well. Who knew where this might end?

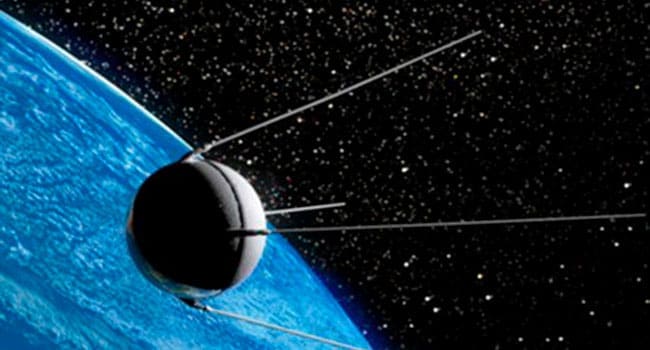

Although Sputnik may look very modest to 21st century eyes, it was a revelation in 1957. It seemed to herald the dawning of a new world.

Sputnik, a polished metal sphere 58 cm in diameter, travelled in a low orbit sending radio signals back to Earth via its four external antennas. Moving at a speed of approximately 29,000 km/h, it completed a full orbit every 96 minutes or so.

Then the Soviets upped the ante a month later, launching Sputnik 2 on Nov. 3. This was a bigger, more sophisticated craft and actually carried a dog – Laika – as the first living creature to venture into space. Unsurprisingly, the American panic intensified.

U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower was surprised, even bemused, by the media and public reaction. He saw it as out of sync with reality. To him, space was not a particular priority.

At his Oct. 9, 1957, press conference, Eisenhower was presented with an array of Sputnik-inspired questions, all implying concern about the purported threat to American security. The prospect of rockets being mounted on satellites and fired from space was one of them.

NBC’s Hazel Markel wondered whether in light of “the Russian satellite whirling about the world, you are not more concerned nor overly concerned about our nation’s security?”

Eisenhower’s reply: “… not one iota.”

Eisenhower, mind you, had access to information that wasn’t generally available. Since the summer of 1956, the U-2 surveillance aircraft had been secretly flying over the Soviet Union at a height of roughly 21 km and photographing everything in its path. From this, Eisenhower had a more realistic and less fanciful idea of what Soviet military capabilities were.

As you’d expect, though, there was a demand for more spending. Historian Jean Edward Smith recounts it this way: “The Joint Chiefs clamoured for massive increases in the defence budget, civil defence officials mounted an urgent drive to construct bomb shelters nationwide, the academic community pressed for more funds for scientific research, and the Democrats – believing that they had found a chink in Ike’s armour – ballyhooed the missile gap and America’s unpreparedness.”

For one ambitious politician – John F. Kennedy – the “missile gap” became a major campaign talking point, another piece of evidence for the need to “get America moving again.” However, within months of taking office in 1961, the Kennedy administration acknowledged the gap’s fictitious nature and it quickly disappeared from public discourse.

Sputnik also added fuel to the evolving intellectual notion that American life had taken a wrong turn. It had, so the theory went, become “soft” and preoccupied with “mindless consumerism.”

Published in 1957, Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders pointed an accusatory finger at the advertising industry. Using motivational research and “subliminal projection,” advertisers were manipulating Americans to buy stuff they neither needed nor really wanted. Rather than being benign, the mass consumption economy was creating a host of social pathologies.

The following year, John Kenneth Galbraith took up the cause with The Affluent Society. Galbraith’s thesis argued that the U.S. had become characterized by “private opulence and public squalor.” Private demand for goods and services exceeded the organic needs of food, clothes and shelter, and was being artificially propelled by advertising. To correct this, society needed to be rebalanced to create a larger public sector that would focus resources on more meaningful things.

It was in this context of panic, Cold War competition and the search for a significant public purpose that President Kennedy put his chips down on May 25, 1961: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

Eight years later, having won the space race by doing just that, Americans largely lost interest.

Maybe Eisenhower was right about priorities.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.