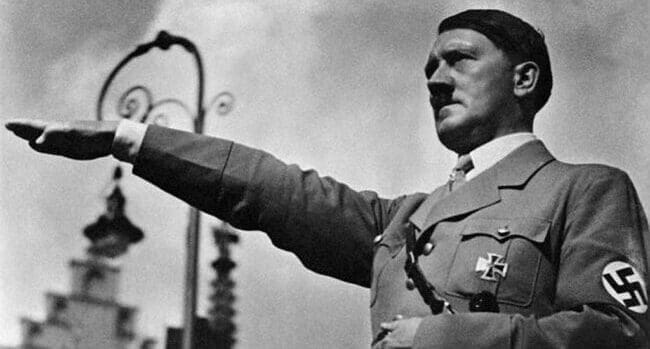

The question of what Germans really thought of Adolf Hitler has been kicking around for as long as I can remember.

The question of what Germans really thought of Adolf Hitler has been kicking around for as long as I can remember.

Were Germans hoodwinked, intimidated or broadly supportive? Or was it perhaps some combination of all three?

Robert Gellately is a Canadian historian who has written extensively on Nazi Germany. And his latest book, Hitler’s True Believers, takes a crack at the question.

Gellately notes that the building blocks for Hitler’s worldview predated his arrival on the scene. Radical nationalism, socialism and anti-Semitism were already established features of the German socio-political landscape.

Then stir in Hitler’s quest for expanded “living space” (at the expense of eastern neighbours) and spice the mixture with a lost war, rampant inflation, economic depression and a badly fractured polity. You wind up with a lot of dry tinder just waiting for the appropriate spark.

Adolf Hitler’s fateful mistake by Pat Murphy

Progressive noses often get out of joint when socialism is identified as part of the Nazi-facilitating mix. But in Germany’s last free elections, over 70 per cent of the vote went to parties with “socialist” or “communist” in their titles. Socialism, in one form or another, was in the German air.

And the Nazis – short for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party – tapped into this milieu. Their version of socialism may have been different from that of the Social Democratic Party or the Communist Party, but it also eschewed anything to do with libertarian or laissez faire economics.

National Socialism didn’t countenance expropriating industry or collectivizing agriculture. That was the Soviet model, which the Nazis considered to be misguided or worse.

National Socialism didn’t countenance expropriating industry or collectivizing agriculture. That was the Soviet model, which the Nazis considered to be misguided or worse.

Private property, in the Nazi view, was “the foundation of all human culture.” Indeed, “the quest for private property was a characteristic that separated the higher from the lower races.”

There was a catch, though.

While individuals had the right to own property, they weren’t free to do whatever they wanted with it. Property came with duties and had to serve the community.

Community – defined racially – was a concept the Nazis were big on.

Writing in 1928, Hitler called for “a community of the people who are connected by blood, united by language, and subject to the same collective fate.” Going further, “the National Socialists are not Marxists, but they are socialists, because they fight for the entire German people, not for an estate, a profession, a religion.”

After the Nazis came to power in January 1933, their pursuit of this communitarian ethos was expressed via a range of programs, some of which were driven through Nazi-affiliated organizations.

There were visits to factories by theatrical troupes and symphony orchestras; arranged vacation trips for workers; a Mother and Child scheme to support families; and a plan to develop an inexpensive family automobile – the Volkswagen – that ordinary people could aspire to own via a four-year savings contract.

Domestically, the Nazi approach was a blend of carrots and sticks. Gellately describes it as resting on three pillars: popularity, tradition and coercion.

Preferably, Germans would be inspired to join the great awakening and restore the authentic national soul. But, to quote from a note-taker at one of Hitler’s private talks, “anyone who doesn’t turn, will be bent.”

How, then, did all this resonate with the broad mass of the German people?

From less than three per cent of the vote in 1928, the Nazis rocketed to over 37 per cent in July 1932. And although they dropped to 33 per cent in November, they were easily the largest party in both 1932 elections.

Yes, it’s true that Hitler never won an absolute majority in a free and fair election. But bear in mind that the German polity was highly splintered. No fewer than 14 parties won seats in both July and November 1932.

Assessing Hitler’s popularity must always be tempered by an awareness of the coercive aspect. Rival political parties were banned after the Nazis came to power and camps were established for the ostensible re-education of those deemed subversive to the new order.

Still, Gellately believes that many, maybe most, ordinary Germans enthusiastically signed on for the program. Young people were particularly susceptible to the euphoria and excitement. It has always been thus.

Tellingly, a post-war 1948 opinion survey indicated that 57 per cent of West Germany’s adult population believed National Socialism had been a good idea that was just poorly implemented.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here. You must be a Troy Media Marketplace media subscriber to access our Sourcebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.